BLESSED RAMADAN 2026!

TO ALL MUSLIMS IN THE NETHERLANDS AND THE WORD, I WISH A BLESSED AND HAPPY RAMADAN!

Kind greetings/Astrid Essed

BLESSED RAMADAN 2026!

TO ALL MUSLIMS IN THE NETHERLANDS AND THE WORD, I WISH A BLESSED AND HAPPY RAMADAN!

Kind greetings/Astrid Essed

Reacties uitgeschakeld voor Blessed Ramadan 2026!

Opgeslagen onder Divers

GEZEGENDE RAMADAN 2026!

AAN ALLE ISLAMITISCHE LEZERS VAN MIJN WEBSITE EN

ANDERE MOSLIMS IN NEDERLAND EEN GEZEGENDE EN BETEKENISVOLLE RAMADAN TOEGEWENST!

Vriendelijke groeten/Astrid Essed

Reacties uitgeschakeld voor Gezegende Ramadan 2026!

Opgeslagen onder Divers

Naar aanleiding van de oproep om foto’s en documenten van Februaristakers heeft het Stadsarchief veel reacties ontvangen. Zo kwam er in april een schenking binnen met stukken van en over stakingsleider Willem Kraan (1909-1942). Kraan was stratenmaker bij de dienst Publieke werken. Dit dossier bevat onder andere foto’s van Willem Kraan, een ontroerende brief aan zijn gezin die hij op 30 november in gevangenschap heeft geschreven en het bericht van zijn executie.

Naar aanleiding van de oproep om foto’s en documenten van Februaristakers heeft het Stadsarchief veel reacties ontvangen. Zo kwam er in april een schenking binnen met stukken van en over stakingsleider Willem Kraan (1909-1942). Kraan was stratenmaker bij de dienst Publieke werken. Dit dossier bevat onder andere foto’s van Willem Kraan, een ontroerende brief aan zijn gezin die hij op 30 november in gevangenschap heeft geschreven en het bericht van zijn executie.

De ouders van Willem Kraan woonden bij de Nieuwmarkt, vlak bij de Jodenbuurt. Op zondag 23 februari was Willem Kraan daar juist op bezoek toen de Duitsers met grof geweld joden begonnen op te pakken. Huilend vertelde hij zijn vriend Piet Nak later die dag wat hij gezien had. Samen beraamden zij toen het plan voor een proteststaking. De twee fietsten de hele stad door om collega’s op de been te krijgen. Ze wilden eerst de tram, de Stadsreiniging of zelfs de hele dienst Publieke Werken plat krijgen. Dan zou de rest van Amsterdam vanzelf volgen. Ze overlegden ook met de Communistische Partij. Willem Kraan en Piet Nak waren zelf allebei lid van de partij, die door de Duitsers verboden was. Ook na de staking bleef Kraan actief in het verzet. Op zestien november 1941 werd hij gearresteerd. Een jaar later werd hij samen met 32 anderen op het vliegveld Soesterberg geëxecuteerd.

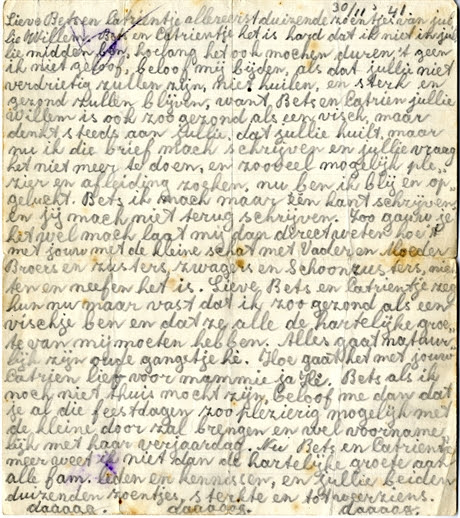

Brief uit de gevangenis van Willem Kaan, 30 november 1941.

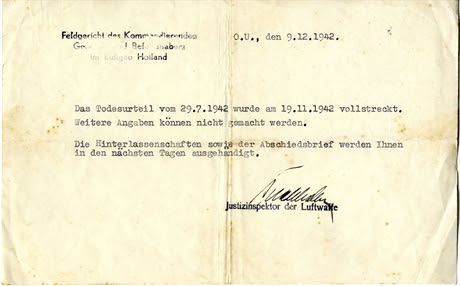

Bericht van executie, 9 december 1942.

AFSCHEIDSBRIEF VAN WILLEM KRAAN VOOR ZIJN EXECUTIE DOORDE DUITSERS.GESCHREVEN OP 19 NOVEMBER 1942, DAG VAN ZIJN EXECUTIE/WILLEM KRAAN WAS EEN VAN DE INITIATIEFNEMERS VAN DEFEBRUARISTAKING/HIJ LIET ZIJN VROUW [BETS] EN DOCHTERTJE TRIENI] BOVEN DE NAZI BRIEF

https://www.amsterdam.nl/

ARRESTATIE NAAR NEDERLAND GEVLUCHTE DUITSEJODEN IN JUNI 1940http://nl.wikipedia.org/

PROTESTEERT TEGEN DE

De Nazi’s hebben Zaterdag en Zondag, en Maandag is dit voortgezet, als beesten in de wijken met veel Joodse bevolking huisgehouden.

Honderden Grüne Feldpolizei kwamen zwaar bewapend plotseling de oude binnenstad en andere wijken binnenvallen. Razend, tierend, ranselend en schietend stortten zij zich met hun bewapende overmacht op de weerloze mannen, vrouwen en kinderen.

Honderden jonge Joden werden met ruw geweld en volkomen willekeurig van de straat in arrestantenwagens gesmakt en weggevoerd naar een onbekend verschrikkingsoord.

D A T I S D E N A Z I – W R A A K

Voor de kloeke zelfverdediging, die de W-A. pogromhelden 2 weken geleden deed afdruipen en waarbij de W.A.-bandiet Koot als terrorist het leven liet.

Dat is het ploertige antwoord op de massa-verontwaardiging en de massa-protest-demonstratie van het Amsterdamse volk tegen de Joden-pogrom.

Dat is vooral het gevolg van de groot-kapitalistische “bemiddeling” van Asscher, Saarlouis en Cohen, die kruiperig de schuld der Joden aanvaardden en verdere krachtige verdedidingsmaatregelen en strijd de kop poogden in te drukken door het voor te stellen, dat nu weer “rust” zou intreden. Deze groot-kapitalisten zijn bang voor het opleggen van een zoengeld en hun duiten zijn hun liever dan het Joodse werkende volk!

De, ook door de Duitse soldaten, gehate S.S. en Grüne Feldpolizei verrichten dit smerige werk met ware wellust. Hier was het uitschot en het scrapuul van het Duitse volk aan het werk. De laffe W.A. slungels het uitschot van ons volk, die nu ontbraken, moeten van dit gespuis leren, hoe de terreur tegen het werkende volk moet worden toegepast.

| Deze jodenpogroms zijn een aanval op het gehele werkende volk ! ! ! | |

| Zij zijn een inzet voor een verder te verscherpen onderdrukking en terreur ! ! ! Zij moeten de weg effenen voor de machtsgreep van de door elke Nederlander gehate Mussert ! ! ! |

|

| WERKEND VOLK VAN AMSTERDAM, KUNT GIJ DIT DULDEN ?? | |

| N e e n , d u i z e n d m a a l N E E N ! ! ! | |

| HEBT GIJ DE MACHT EN DE KRACHT DEZE AFSCHUWELIJKE TERREUR VERDER TE VERHINDEREN ?? | |

| J a , d a t h e b t g i j ! ! ! |

De Amsterdamse metaalbewerkers hebben getoond hoe het moet. Zij staakten eensgezind tegen hun gedwongen uitzending naar Duitsland. En de dwang van de Duitse militaire macht moest het tegen dit verzet afleggen!

In één dag behaalden de metaalarbeiders de overwinning!!

LAAT U DUS DOOR DE PLOMPE DUITSE SOLDATENLAARS NIET INTIMIDEREN !!

ORGANISEERT IN ALLE BEDRIJVEN DE PROTEST-STAKING ! ! !

VECHT EENSGEZIND TEGEN DEZE TERREUR ! ! !

EIST DE ONMIDDELLIJKE VRIJLATING VAN DE GEARRESTEERDE JODEN ! ! !

EIST DE ONTBINDING VAN DE W.A-TERREURGROEPEN ! ! !

ORGANISEERT IN DE BEDRIJVEN EN IN DE WIJKEN DE ZELFVERDEDIGING ! ! !

WEEST SOLIDAIR MET HET ZWAAR GETROFFEN JOODSE DEEL VAN HET WERKENDE VOLK ! ! !

ONTTREKT DE JOODSE KINDEREN AAN HET NAZI-GEWELD, NEEMT ZE IN UW GEZINNEN OP ! ! ! !B E S E F T D E E N O R M E K R A C H T V A N U W E E N S G E Z I N D E D A A D ! ! ! ! ! Deze is vele malen groter dan de Duitse militaire bezetting! Gij hebt in Uw verzet ongetwijfeld een groot deel van de Duitse arbeiders-soldaten met u ! ! ! !STAAKT !!! STAAKT !!! STAAKT !!! Legt het gehele Amsterdamse bedrijfsleven één dag plat, de werven, de fabrieken, de ateliers, de kantoren en banken, gemeente-bedrijven en werkverschaffingen ! !Dan zal de Duitse bezetting moeten inbinden! Dan hebt gij een slag toegebracht aan het monsterachtig plan, Mussert aan de macht te helpen! Dan verhindert ge een verdere leegplundering van ons land!! Dan krijgt ge de kans Woudenberg uit het N.V.V. te jagen ! ! !

STELT OOK OVERAL UW EISEN VOOR VERHOGING VAN LOON EN STEUN ! !W E E S T E E N S G E Z I N D ! ! W E E S T M O E D I G ! ! !STRIJDT FIER VOOR DE VRIJMAKING VAN ONS LAND ! ! ! !

| KAMERADEN, Geeft dit manifest na gelezen te hebben verder door! Plakt het op waar gij kunt doch d o e h e t v o o r z i c h t i g ! |

REEDS TOONDEN DE GEMEENTE- EN ANDERE GROTE BEDRIJVEN HOE HET MOET ! ! !V O L G T A L L E N H U N V O O R B E E L D ! ! ! !MANIFEST FEBRUARISTAKINGhttp://www.

STANDBEELD DE DOKWERKER, TER HERDENKING AAN DEDAPPERE FEBRUARISTAKERS, DIE IN GEWEER KWAMENTEGEN DE ANTI JOODSE MAATREGELEN VAN DE DUITSENAZI BEZETTER

LEZERS!

Ik heb het hier over de door de toenmalige CPN [CommunistischePartij Nederland] georganiseerde tweedaagse staking tegen de Duitse Nazi Bezetter. [1]

Een moedige staking van Amsterdamse arbeiders tegen de beginnende Jodenvervolging, een staking, die later door anderen werd overgenomen en zich uitbreidde naar andere steden.

De staking duurde twee dagen [25 en 26 februari] voordat de door de staking verraste Duitsers en hun handlangers met grof geweld ingrepen.

Aanleiding dus:

Het begin van de Jodenvervolging.

Razzia’s tegen de Joodse bevolking. [2]Het was het GVB personeel [trampersoneel], dat begon.Gaandeweg breidde de staking zich als een olievlek uit inAmsterdam en ook in de Zaanstreek en andere steden werd gestaakt. [3]

STA STILBIJ DE TEKST VAN HET STAKINGSMANIFESTLEZERS, LAAT HET OP U INWERKEN!

”De Nazi’s hebben Zaterdag en Zondag, en Maandag is dit voortgezet, als beesten in de wijken met veel Joodse bevolking huisgehouden.

Honderden Grüne Feldpolizei kwamen zwaar bewapend plotseling de oude binnenstad en andere wijken binnenvallen. Razend, tierend, ranselend en schietend stortten zij zich met hun bewapende overmacht op de weerloze mannen, vrouwen en kinderen.

Honderden jonge Joden werden met ruw geweld en volkomen willekeurig van de straat in arrestantenwagens gesmakt en weggevoerd naar een onbekend verschrikkingsoord.

D A T I S D E N A Z I – W R A A K

Voor de kloeke zelfverdediging, die de W-A. pogromhelden 2 weken geleden deed afdruipen en waarbij de W.A.-bandiet Koot als terrorist het leven liet.

Dat is het ploertige antwoord op de massa-verontwaardiging en de massa-protest-demonstratie van het Amsterdamse volk tegen de Joden-pogrom.

Dat is vooral het gevolg van de groot-kapitalistische “bemiddeling” van Asscher, Saarlouis en Cohen, die kruiperig de schuld der Joden aanvaardden en verdere krachtige verdedidingsmaatregelen en strijd de kop poogden in te drukken door het voor te stellen, dat nu weer “rust” zou intreden. Deze groot-kapitalisten zijn bang voor het opleggen van een zoengeld en hun duiten zijn hun liever dan het Joodse werkende volk!

De, ook door de Duitse soldaten, gehate S.S. en Grüne Feldpolizei verrichten dit smerige werk met ware wellust. Hier was het uitschot en het scrapuul van het Duitse volk aan het werk. De laffe W.A. slungels het uitschot van ons volk, die nu ontbraken, moeten van dit gespuis leren, hoe de terreur tegen het werkende volk moet worden toegepast.

Deze jodenpogroms zijn een aanval op het gehele werkende volk ! ! !

Zij zijn een inzet voor een verder te verscherpen onderdrukking en terreur ! ! !

Zij moeten de weg effenen voor de machtsgreep van de door elke Nederlander gehate Mussert ! ! !

WERKEND VOLK VAN AMSTERDAM, KUNT GIJ DIT DULDEN ??

N e e n , d u i z e n d m a a l N E E N ! ! !

HEBT GIJ DE MACHT EN DE KRACHT DEZE AFSCHUWELIJKE TERREUR VERDER TE VERHINDEREN ??

J a , d a t h e b t g i j ! ! !

De Amsterdamse metaalbewerkers hebben getoond hoe het moet. Zij staakten eensgezind tegen hun gedwongen uitzending naar Duitsland. En de dwang van de Duitse militaire macht moest het tegen dit verzet afleggen!

In één dag behaalden de metaalarbeiders de overwinning!!

LAAT U DUS DOOR DE PLOMPE DUITSE SOLDATENLAARS NIET INTIMIDEREN !!”

ZIE NOOT 4

ACHTERGROND/HET BEGIN

Vanaf de Duitse nazi bezetting van Nederland werden langzaam, maar zeker steeds meer anti Joodse maatregelen ingevoerd [5], waarbij de nazi’s in hun terreur tegen de Joden werden geholpen door de WA, de paramilitaire knokploeg van de pro Duitse NSB. [6]

Deze WA terroriseerde en intimideerde Joden, sloeg ze in elkaar en intimideerde weigerachtige niet Joodse winkeliers, het door de bezetter verplichte bord ´´Voor Joden verboden´´op te hangen. (7)

Maar de Joden en niet Joodse solidaire mensen, vooral communisten en hun organisaties (stevig in het verzet geworteld)kwamen in het geweer en richtten zelfverdedigingsgroepen op, die de strijd met deze gangsters aangingen. [8]Dat escaleerde vanwege de toenemende WA provocaties(vaak geholpen door Duitse militairen), waarbij een WA man, Koot, om het leven kwam. (9)

Deze dood werd door de Duitse bezetter aangegrepen om de anti Joodse maatregelen te intensiveren.

De Joodse buurt in Amsterdam werd op 12 februari 1941 hermetisch van de buitenwereld afgesloten [10] (een dag na de confrontatie tussen WA gangsters en de Joodse en door hen gesteunde communistische verdedigingsploegen, waarbij Koot om het leven kwam) en onder druk van de bezetter werd de Joodse Raad opgericht, die in feite het vuile werk van de bezetter moest opknappen. (11)

Bij een Duitse inval in een door Duits-Joodse vluchtelingen gedreven ijssalon Koco, waarbij behoorlijk werd gevochten, werden de eigenaren en enkele verdedigers van de ijssalon gearresteerd. [12]

Dit was voor de bezetter aanleiding, helemaal los te gaan.

De mensenjacht begon.

Op 22 en 23 februari werden de eerste twee grote razzia´s onder

de Joodse bevolking gehouden, waarbij 427 Joodse mannen werden opgepakt en naar het concentratiekamp Mauthausen werden gedeporteerd. [13]

FEBRUARISTAKINGSTAAKT! STAAKT! STAAKT!

En toen was de maat vol!

De door de bezetter illegaal verklaarde CPN [Communistische Partij Nederland] besloot in actie te komen en de staking, die toch al gepland was [maar niet doorgegaan op 18 februari] nu massaal op te zetten, om zo te protesteren tegen de Jodenvervolgingen. Het landelijke partijbestuur en het bestuur van het District Amsterdam besloten vervolgens over te gaan tot een staking op 25 en 26 februari 1941.

‘

Ter voorbereiding op de staking organiseerde de ondergrondse CPN op 24 februari een korte openluchtvergadering van ongeveer 400 Amsterdamse leidinggevende verzetsfunctionarissen op de Noordermarkt in de Jordaan.

Stratenmaker Willem Kraan verkondigde hier het besluit tot staken, wat werd ondersteund door mede initiatiefnemers tot destaking, de verzetsmannen Piet Nak en Dirk van Nimwegen .[14]

Massale steun kreeg deze staking, die begon met het Openbaar Vervoer en de Gemeentereiniging en oversloeg naar andere sectoren. [15]

Van Amsterdam sloeg de staking over naar Zaandam, Haarlem, Velsen,

Ze hebben het twee volle dagen opgenomen tegen de bezetter.Toen werd de staking met geweld neergeslagen, vooral CPN’ers[die een groot aandeel in de staking hadden] vervolgd, gearresteerden een aantal geexecuteerd. [17]

Ze streden tegen antisemitisme, racisme en de uitsluitingvan mensen op grond van hun afkomst.

HULDE!

TOEN EN NU

”HYENA’S, OMVOLKING, ”ACHTERLIJKE ISLAMITISCHE ZANDBAKLANDEN”, ”AFRIKAANSE INDRINGERS”, ”DRIE BEESTEN

VAN SURINAAMSE AFKOMST”, ”DOBBERNEGERS”, ”ZIN OM

JODEN TE VERGASSEN”

MEER

HET OPRUKKENDE FASCISME

Hulde dus aan de dapperen, die zich niet neerlegden bij rassenwaan, vervolging en tirannie.

MAAR:

Waarom die Herdenking door te trekken naar deze Tijd?

Omdat het Hoog nodig is

Omdat het fascisme hard om zich heen grijpt, in Europa, in Nederland

In deze Tijd waarin wij leven!

De Zondebokken van nu zijn moslims, Marokkanen, vluchtelingen,

niet-westerse allochtonen.

Maar ook de Joden.

Laten we bij de eerste Zondebokken-targets beginnen [ik probeer het kort

te houden]

Er is een Partij, de PVV, met haar Leider Wilders, die er vanaf haar oprichting haar Levenswerk van gemaakt heeft, haat en angst te zaaien tegen de Islam als religie [18], Marokkanen [19], niet westerse

allochtonen, vluchtelingen.

Het voert te ver alle voorbeelden daarvan te noemen, maar enkele in de titeltekst heb ik al genoemd:

PVV Leider Wilders noemde destijds 3 verdachten van een taximoord

”drie Beesten van Surinaamse afkomst” [20] en fulmineerde in diezelfde

Column tegen ”Criminele Allochtonen” [21], alsof er geen criminele autochtonen

zouden bestaan.

Deze zelfde Wilders is trouwens ook een groot voorstander van ”administratieve detentie” [detentie zonder vorm van proces” [22]

tegen potentiele terreurverdachten.

Ook de verwijzing naar ”omvolking” van Nederland [23], een fascistische

term, is uit Wilders” koker, zoals veel, veel meer.

Zoals ”achterlijke islamitische zandbaklanden” [24]

Zijn PVV Tweede Kamergenoot en Compaan Markuszower kan

er ook wat van:

Zo sprak hij over ”buitenlandse indringers uit Afrika en

het Midden-Oosten” [25] en dat Nederland is volgepropt met

””de verkeerde buitenlanders, die op onze welvaartsstaat parasiteren door en masse

niet te werken en onze Bijstandspotten op te eten,

die onze straten onveilig maken, die de gewone

Nederlander op de woningmarkt verdringen, die de

kwaliteit van het onderwijs aantasten…..”[26]

Ook is Markuszower Kampioen bangmaken:

Een uitspraak van hem

””En weet u, voorzitter, hoeveel migranten uit Afrika

en het Midden-Oosten nog naar onze regio willen komen, de komende jaren?

Dat zijn honderden miljoenen, zo niet een

miljard mensen” [27]

Niet alleen een complete leugen [28], maar leidend

tot bangmakerij.

Haatzaaierij

Dat deze Markuszower ook nog wel eens iets goeds doet

[zo kwam hij op voor een door racistische jongeren belaagde

Surinaamse onderneemster] [31] maakt zijn valse

haatzaaierij natuurlijk niet goed.

Vluchtelingen zijn door Wilders ook al voor ”hyena’s uitgemaakt [32–waar doet DAT nou aan denken [33] en dan nog niet te vergeten Wilders” ”Minder-minder” uitspraak [34] en het neerzetten van Syrische vluchtelingen als ”testosteronbommen”, die kennelijk geen ander Levensdoel zouden

hebben dan Europese vrouwen en meisjes aanranden en verkrachten [35]

Geen wonder, dat deze PVV terecht extreem rechts en fascistisch genoemd wordt. [36]

Fascisme is een Ziekte, die de samenleving aantast:

Geen wonder, dat Wilders en co navolgers krijgen, van wie de ene weer

gevaarlijker is dan de andere:

Zo verwees vluchtelingenhater en anti-semiet Annabel Nanninga [voormalig

politica van het eveneens fascistische Forum voor Democratie van leider Thierry Baudet [37] en huidig politica van het tegen fascisme aanleunende JA 21,

dat zij mede heeft opgericht [38] naar Afrikaanse vluchtelingen als ”Dobbernegers” [39] en liet ze zich onversneden anti-semitisch uit

met de volgende uitspraak ”Mein Kampf, je leest 6 bladzijden en hebt

meteen zin om Joden te vergassen [40]

TSJAAAA………………..

PVV GROOTSTE PARTIJ!

En dat zou allemaal [hoe eng ook] nog niet zo’n ramp zijn,

als al die hatelijkheden waren geuit door splinterpartijtjes

VERGEET HET MAAR

Bij de 22 november verkiezingen anno Donini 2023 kopte de PVV in

met maar liefst 36 Kamerzetels, waarmee ze de grootste politieke Partij in

Nederland werd! [41]

En of nu alle PVV stemmers onversneden racisten zijn of niet [42], doet

er eigenlijk niet zo toe,

Ze namen in ieder geval de vreemdelingenhaat van de PVV

op de koop toe.

Trouwens, uit onderzoek is gebleken, dat de meeste PVV kiezers wel

degelijk vanwege ”afkeer van migranten” op de PVV

hebben gestemd. [43]

DONKERE WOLKEN

OPRUKKEND FASCISME IN NEDERLAND EN EUROPA!

Zoals u weet Lezers, gedenk ik ieder jaar de Februaristaking

in Woord en Daad.

U leest dat op mijn website

Een jaar na mijn vorige Website Herdenking [44]

is het alleen maar erger geworden!

PVV regeert ondanks alle onderlinge strubbels [45]

volop met de BBB van Caroline van der Plas [46],

de VVD en de NSC. [47]

Weet u nog?

Laatstgenoemde Partij die aanvankelijk nog pertinent had

geweigerd, bij monde van leider Ontzigt, met de PVV in zee te gaan….[48]

Het kan verkeren……………….

Zie voor meer Informatie over dit Rampen/Fascistenkabinet Schoof [49],

mijn website pagina [50]

Dan zullen jullie lezen, lezers, hoe ”gewoon” dit door dit kabinet

verspreide Fascisme al is geworden [51]

Hoe de vluchteling de Absolute Zondebok is [52]

[For the moment, het zal niet bij de vluchtelingen blijven….]

Hoe Ongeluksprofeten als de racistische anti immigratie

”deskundige” Jan van Beek, hun Gif via de media keer

op keer verspreiden…………….[53]

DUITSLAND/VICTORIE VAN HET KWAAD

Nu is er in grote delen van Europa een ruk richting fascisme [54],

maar het griezeligste vind ik Duitsland, Bakerland van de Holocaust [55]

Daar is iets griezeligs aan het gebeuren, omdat de extreem-rechtse AFD

daar bij de verkiezingen de tweede partij is geworden [56]

Een Partij met neo-nazi’s en banden met neo-nazi’s! [57]

Ook is Duitsland een land geworden waar neo-nazi’s openlijk

gewelddadig opereren! [58]

I rest my case…………….

HEDEN

Nu is het Fascistenkabinet gevallen

https://www.astridessed.nl/

En inmiddels is het niet fascistenkabinet Jetten I aangetreden, waarover\

ook een hoop te zeggen is

https://peterstormt.nl/2026/

Maar de strijd tegen het Fascisme gaat onverminderd door!

SLOT

Onze Strijd gaat door, welke Regering, Welk Kabinet, Welke Factie,

Welk Regime dit land ook gaat regeren!

Waar onderdrukking is, is Verzet

Bereid jullie daarop voor, Fascisten en Fascistenvrienden!

WE WILL NEVER SURRENDER!!!!

Gedenk de Februaristaking

Voer de Strijd

ASTRID ESSED

NOTEN

ZIE VOOR NOTEN 1 T/M 43

NOTEN 44 EN 45

https://www.astridessed.nl/

NOTEN 46 T/M 48

https://www.astridessed.nl/

NOTEN 49 T/M 53

https://www.astridessed.nl/

NOTEN 54 T/M 56

https://www.astridessed.nl/

NOTEN 57 EN 58

https://www.astridessed.nl/

Reacties uitgeschakeld voor 85 JAAR FEBRUARISTAKING/TOEN NIET, NU NIET, NOOIT!

Opgeslagen onder Divers

Reacties uitgeschakeld voor Bridgerton/Lady Violet, her son Anthony and the Siena Rosso Affair/The Beginning

Opgeslagen onder Divers

BRIDGERTON/LADY VIOLET BRIDGERTON EN HAAR RELATIE MET HAAR

Reacties uitgeschakeld voor Bridgerton/Lady Violet en haar zoon Anthony/De diepe, verwrongen liefde van een moeder

Opgeslagen onder Divers

BRIDGERTON/LADY VIOLET BRIDGERTON, HAAR ZOON ANTHONY EN

Reacties uitgeschakeld voor Bridgerton/De Affaire Siena Rosso/Deel EEN

Opgeslagen onder Divers

Reacties uitgeschakeld voor Bridgerton/Fifth Comment/The Siena Rosso Affair/Part Two

Opgeslagen onder Divers

Reacties uitgeschakeld voor Bridgerton/Fourth Comment/The Siena Rosso Affair/Part One

Opgeslagen onder Divers

LADY VIOLET BRIDGERTON AND HER COMPLEX RELATIONSHIP WITH HER

BRIDGERTON/LADY VIOLET AND HER COMPLEX RELATIONSHIP WITH HER ELDEST SON ANTHONY

Reacties uitgeschakeld voor Bridgerton/Astrid Essed about Bridgerton/Lady Violet and her complicated relationship with her eldest son Anthony/Or a Mother’s Failed Love

Opgeslagen onder Divers

Reacties uitgeschakeld voor Bridgerton/Astrid Essed over ”Bridgerton”/Lady Violet en haar gecompliceerde relatie met haar zoon Anthony

Opgeslagen onder Divers