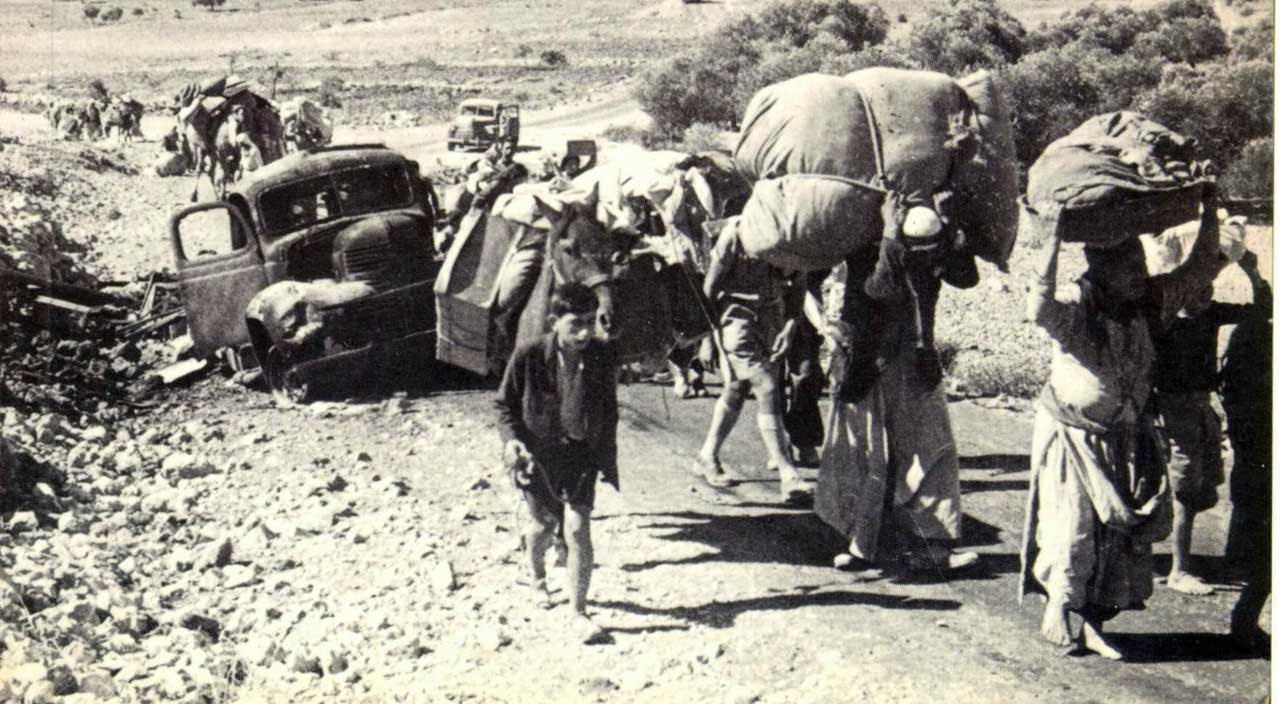

Palestinian Refugees on their way to Lebanon, Oct. 1948.

Palestinian Refugees on their way to Lebanon, Oct. 1948.

Palestinian Refugees on their way to Lebanon, Oct. 1948.

THE HARVEST OF ZIONISMETNIC CLEANSINGS OF PALESTINEhttp://la.indymedia.org/news/2 007/06/201927.phphttps://www.astridessed.nl/200 7disaster-over-palestinethe- refugee-problem-and-the- ideology-of-transfer/

TER ERE VAN ISRAEL’S ONAFHANKELIJKHEIDSDAG/CONCERTGEBOUW AMSTERDAM GEEFT FOUT CONCERT

AANCONCERTGEBOUW AMSTERDAM

Onderwerp: Uw concert [zonder publiek]op 28 april 2020 ter ere van Israel’s Onafhankelijkheidsdag

Geacht Bestuur,

”Al is de leugen nog zo snel, de waarheid achterhaalt ze wel” [1]Ongetwijfeld kent u deze oud-vaderlandse uitdrukking, hier op u van toepassing.

Want wellicht dacht u”Nu met die Coronamaatregelen gewone concerten [met publiek] niet mogelijk zijn, zal een ter ere van Israel gehouden concert niet of nauwelijks opvallen-en dus niet de nodige kritiek uitlokken.”‘Nou, MIS POES, Geacht Bestuur!Vandaar deze brief, die er NIET om liegt en u een stevige, virtuele draai om uw oren geeft!

Want met het faciliteren van dit concert, met of zonder publiek [2] hebt u een eerbetoon gedaan aan bezetting, etnische zuiveringen en massaslachtingen, dit alles gegoten in een neo koloniaal jasje.En kom me niet aan met de smoes, dat uw Bestuur a-politiek zou zijn:U herdenkt en eert hier de ONAFHANKELIJKHEIDSDAG [3] van een land, dat ontstaan is op basis van land en identiteitsroof!Met andere woorden:Gebouwd op Bloed, Zweet en Tranen van een ander volk, namelijk het Palestijnse! [4]

TOELICHTING:’

Die Israelische ”Onafhankelijkheidsdag” is een van de meest doortrapte staaltjes van neo-kolonialistisch geschonden zelfbeschikkingsrecht na de Tweede Wereldoorlog!Ik zeg nadrukkelijk NA de Tweede Wereldoorlog, want voor de Tweede Wereldoorlog, zeker aan het begin van de twintigste eeuw, toen de Israelisch [al werd dat toen nog ”zionistisch” genoemd Joodse kolonisatie van Palestina eenaanvang nam aanvang nam, werd de opdeling van het land van andere volkeren, of de inbeslagname van hun land als gewoon gezien, gebaseerd als dat was op in de 19e eeuw ontwikkelde Westerse superioriteitstheorieeen.

Hiervan zijn de Palestijnen het slachtoffer geworden, want waar het in het kort op neer komt is dat hun land, historisch Palestina [eeuwenlang behorend tot het Ottomaanse Rijk] waarin zij eeuwenlang woonden, over hun ruggen is opgedeeld in een Joods en een Arabisch deel in 1947, bij VN Resolutie 181. [5]

Daaraan voorafgegaan was het aan het eind van de 19e eeuw door de Oostenrijkse journalist Theodor Herzl opgerichte zionistische beweging [6]met als doel het creeren van een Joods Thuisland in Palestina. [7]Dit begon verwezenlijkt te worden door de Balfour Declaratie in 1917 [8], waarbij aan de voorzitter van de zionistische beweging in Groot-Britannie door de toenmalige minister van Buitenlandse Zaken Balfour de belofte werd gedaan van een Joods Thuisland in het toen nog bij het Ottomaanse Rijk behorende Palestina.Palestina, dat alvast in 1916 als een Taart door toenmalige koloniale machten Frankrijk en Groot Britannie in het Sykes-Picot Verdrag aan de Britten was toegewezen.[9]”Grappig” was wat schrijver Arthur Koestler opmerkte over die Balfour Declaration:dat ”“one nation solemnly promised to a second nation the country of a third,” [10]Een buitengewoon rake beschrijving van wat er in werkelijkheid gebeurde.Want het ging al gauw niet meer om de bewoning van Joodse mensen in Palestina [die migratie was vanaf het begin van de twintigste eeuw mondjesmaat en later veel enthousiaster, op gang gekomen], maar om het stichten van een Staat in anderman’s land.Complicerende factor:Dat ”anderman’s land, was eerst een onderdeel van het Ottomaanse Rijk en na de Eerste Wereldoorlog vanaf 1922 ”Mandaatgebied Palestina” [11], met andere woorden een situatie waarin de Palestijnse bevolking geen zelfbeschikking had.Maar het was ook de tijd, dat overal in de kololnieen onafhankelijkheidsbewegingen opkwamen, wat uiteindelijk na WO II leidde tot onafhankelijkheid en zelfbeschikkingsrecht.Maar doordat er deals tussen Groot-Britannie en de zionistische beweging waren gesloten, werd dat zelfbeschikkingsrecht de Palestijnen door de neus geboord en hun land in 1947 over hun ruggen heen, opgedeeld in een Joods en Palestijns gedeelte. [12]Daarna [eind 1947] liepen de spanningen tussen de zionistische organisaties en hun achterban enerzijds en de Palestijnse bevolking anderszijds steeds hoger op, Palestijnen werden toen reeds etnisch gezuiverd [verdreven van huis en haard] en in mei 1948 riep de zionistische leider David Ben Goerion eenzijdig [In VN resolutie 181 werd nog gesproken van het ”toekomstige bestuur van Palestina” de zionistisch-Israelische Staat uit [die eenzijdige uitroeping vieren ze dus nu als ”Onafhankelijkheidsdag] [13]De spanningen liepen verder op, een openlijke strijd brak uit en in de zogenaamde ”Onafhankelijkheidsoorlog” werden meer dan 750 000 Palestijnen etnisch gezuiverd. [14]Een VN bemiddelaar, Graaf Bernadotte, die ten gunste van de Palestijnse vluchtelingen wilde ingrijpen, werd geliquideerd door zionistische terroristen. [15]Van Bernadotte is bekend, dat hij gezegd heeft”It would be an offence against the principles of elemental justice if these innocent victims of the conflict were denied the right to return to their homes while Jewish immigrants flow into Palestine, and, indeed, at least offer the threat of permanent replacement of the Arab refugees who have been rooted in the land for centuries” [16]

EPILOOG

Dat u niet van al die details/voorgeschiedenis op de hoogte bent, neem ik u op zich niet kwalijk.Echter:Wanneer u een de ”Onafhankelijkheidsdag” van een land eert, hoort u zich eerst in de voorgeschiedenis ervan te verdiepen, om in dit geval tot de conclusie te komen, dat niet Israel een onafhankelijkheidsdag had moeten vieren, maar de Palestijnen!

Maar wat ik u WEL in hoge mate aanreken, is dat u een concert organiseert ter ere van een land, dat zich -en DAT hoort u WEL te weten, al 53 jaar schuldig maakt aan de meest universele schendingen van mensenrechten.Namelijk bezetting, onderdrukking, oorlogsmisdaden. [17]Een land, dat letterlijk land heeft gestolen in bezet Palestijns gebied door het bouwen van nederzettingen, die in strijd zijn met het Internationaal Recht [18]En die nederzettingen zijn niet alleen een hap uit bezet Palestijns gebied, Israel gaat vrolijk door met de uitbreiding ervan. [19]

De onafhankelijkheidsdag van een dergelijk land eren is de legitimatie van bezetting, onderdrukking, etnische zuiveringen.

Met het geven van een concert, onder deze condities, getuigt u van het totaal ontbreken van elementaire beschaving en gebrek aan respect voor het Internationaal Recht.Weet u wel, hoe vaak Israel VN Resoluties aan zijn laars gelapt heeft? [20]

En daarvan, van die bezetting en onderdrukking, hoort u anno 2020 op de hoogte te zijn.

Ik eis dan ook van u, dat het de laatste keer is geweest, dat u een concert ter ere van Israel gegeven hebt.

Dat dit zonder publiek heeft plaatsgehad, is meer dan passend.

Een dikke NUL voor uw handelwijze.

BAH!

Vriendelijke groetenAstrid EssedAmsterdam

NOTEN

[1]

WOORDEN.ORG

al is de leugen nog zo snel de waarheid achterhaalt ze wel (=leugens komen altijd uit)

https://www.woorden.org/spreekwoord.php?woord=al%20is%20de%20leugen%20nog%20zo%20snel%20de%20waarheid%20achterhaalt%20ze%20wel

[2]

JEWISH TELEGRAPH AGENCYISRAEL’S INDEPENDENCE DAY GETS FIRST CELEBRATION AT THE DUTCH ROYAL CONCERT HALL-WITHOUT A CROWD28 APRIL 2020

https://www.jta.org/quick-reads

AMSTERDAM (JTA) — This year was supposed to be the first time that Israel’s Independence Day was celebrated in a public concert at the main royal concert hall in the Netherlands.

Planned for April 28 at the main hall of the 134-year-old Royal Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, the concert was to feature well-known artists including Shuly Nathan playing her iconic “Jerusalem of Gold” before an expected sellout crowd of 2,000 spectators.

The event was canceled because of the coronavirus, yet Israel’s 72nd birthday was still celebrated at the Concertgebouw thanks to the determination of the concert’s producer, Barry Mehler, who also produces the annual Hanukkah concert at the hall.

Mehler, a U.S.-born professional singer and cantor who has been living in Amsterdam since 1989, in recent days recorded five tracks in Israel’s honor with a group of musicians from the Jewish Amsterdam Chamber Ensemble. They played in an empty hall while observing social distancing protocols.

The setup used the empty hall as background to haunting effect: The musicians are facing the camera with their backs to the red velvet-upholstered seats.

The tracks, which Mehler has shared online, include an instrumental rendition of “Hatikvah,” Israel’s national anthem, and the melancholic song “Mishehu,” or “Someone,” written by Matti Caspi, for Israel’s Memorial Day, which symbolically precedes the nation’s Independence Day.

“Performing in the main hall of the Concertgebouw is an honor reserved to few professional musicians, and more so, that they have allowed us to record parts of our canceled concert,” Mehler, 54, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.BY CNAAN LIPHSHIZ

EINDE ARTIKEL

TWEEDE ARTIKEL:

THE TIMES OF ISRAELISRAEL’S INDEPENDENCE CELEBRATED IN EMPTY DUTCH MUSIC HALL29 APRIL 2020

https://www.timesofisrael.com/israels-independence-celebrated-in-empty-dutch-music-hall/

What should have been first public concert to mark anniversary of Jewish state’s founding is canceled due to coronavirus lockdown, but organizers record performance anyway

AMSTERDAM (JTA) — This year was supposed to be the first time that Israel’s Independence Day was celebrated in a public concert at the main royal concert hall in the Netherlands.

Planned for April 28 at the 134-year-old Royal Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, the concert was to feature well-known artists including Shuly Nathan playing her iconic “Jerusalem of Gold” before an expected sellout crowd of 2,000 spectators.

The event was canceled because of the coronavirus, yet Israel’s 72nd birthday was still celebrated at the Concertgebouw thanks to the determination of the concert’s producer, Barry Mehler, who also produces the annual Hanukkah concert at the hall.

Mehler, a US-born professional singer and cantor who has been living in Amsterdam since 1989, in recent days recorded five tracks in Israel’s honor with a group of musicians from the Jewish Amsterdam Chamber Ensemble. They played in an empty hall while observing social distancing protocols.

The setup used the empty hall as background to haunting effect: The musicians are facing the camera with their backs to the red velvet-upholstered seats.

The tracks, which Mehler has shared online, include an instrumental rendition of “Hatikvah,” Israel’s national anthem, and the melancholic song “Mishehu,” or “Someone,” written by Matti Caspi, for Israel’s Memorial Day, which symbolically precedes the nation’s Independence Day.“Performing in the main hall of the Concertgebouw is an honor reserved to few professional musicians, and more so, that they have allowed us to record parts of our canceled concert,” Mehler, 54, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

[3]

”Independence Day (Hebrew: יום העצמאות Yom Ha’atzmaut, lit. “Day of Independence”) is the national day of Israel, commemorating the Israeli Declaration of Independence in 1948. The day is marked by official and unofficial ceremonies and observances.

Because Israel declared independence on 14 May 1948, which corresponded with the Hebrew date 5 Iyar in that year, Yom Ha’atzmaut was originally celebrated on that date. However, to avoid Sabbath desecration, it may be commemorated one or two days before or after the 5th of Iyar if it falls too close to the Jewish Sabbath. Yom Hazikaron, the Israeli Fallen Soldiers and Victims of Terrorism Remembrance Day is always scheduled for the day preceding Independence Day.

In the Hebrew calendar, days begin in the evening.[2] The next occurrence of Yom Haatzmaut will take place on 28–29 April 2020”

WIKIPEDIA

INDEPENDENCE DAY (ISRAEL)

[4]

CIVIS MUNDI

ZWEEDSE FOTOGRAAF WINT WORLD PRESS PHOTO 2012.

MISDADEN ISRAELISCHE POLITIEK IN BEELD GEBRACHT

ASTRID ESSED

[5]

”The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as Resolution 181 (II)

WIKIPEDIA

UNITED NATIONS PARTITION PLAN FOR PALESTINE

GENERAL ASSEMBLY

29 NOVEMBER 1947

RESOLUTION 181. FUTURE GOVERNMENT OF PALESTINE

https://unispal.un.org/DPA/DPR/unispal.nsf/0/7F0AF2BD897689B785256C330061D253 The General Assembly,

Having met in special session at the request of the mandatory Power to constitute and instruct a special committee to prepare for the consideration of the question of the future government of Palestine at the second regular session;

Having constituted a Special Committee and instructed it to investigate all questions and issues relevant to the problem of Palestine, and to prepare proposals for the solution of the problem, and

Having received and examined the report of the Special Committee (document A/364) 1/ including a number of unanimous recommendations and a plan of partition with economic union approved by the majority of the Special Committee,

Considers that the present situation in Palestine is one which is likely to impair the general welfare and friendly relations among nations;

Takes note of the declaration by the mandatory Power that it plans to complete its evacuation of Palestine by 1 August 1948;

Recommends to the United Kingdom, as the mandatory Power for Palestine, and to all other Members of the United Nations the adoption and implementation, with regard to the future government of Palestine, of the Plan of Partition with Economic Union set out below;

Requests that

(a) The Security Council take the necessary measures as provided for in the plan for its implementation;

(b) The Security Council consider, if circumstances during the transitional period require such consideration, whether the situation in Palestine constitutes a threat to the peace. If it decides that such a threat exists, and in order to maintain international peace and security, the Security Council should supplement the authorization of the General Assembly by taking measures, under Articles 39 and 41 of the Charter, to empower the United Nations Commission, as provided in this resolution, to exercise in Palestine the functions which are assigned to it by this resolution;

(c) The Security Council determine as a threat to the peace, breach of the peace or act of aggression, in accordance with Article 39 of the Charter, any attempt to alter by force the settlement envisaged by this resolution;

(d) The Trusteeship Council be informed of the responsibilities envisaged for it in this plan;

Calls upon the inhabitants of Palestine to take such steps as may be necessary on their part to put this plan into effect;

Appeals to all Governments and all peoples to refrain from taking action which might hamper or delay the carrying out of these recommendations, and

Authorizes the Secretary-General to reimburse travel and subsistence expenses of the members of the Commission referred to in Part I, Section B, paragraph 1 below, on such basis and in such form as he may determine most appropriate in the circumstances, and to provide the Commission with the necessary staff to assist in carrying out the functions assigned to the Commission by the General Assembly.

B 2/

The General Assembly

Authorizes the Secretary-General to draw from the Working Capital Fund a sum not to exceed $2,000,000 for the purposes set forth in the last paragraph of the resolution on the future government of Palestine.

Hundred and twenty-eighth plenary meeting

29 November 1947

[At its hundred and twenty-eighth plenary meeting on 29 November 1947 the General Assembly, in accordance with the terms of the above resolution [181 A], elected the following members of the United Nations Commission on Palestine: Bolivia, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Panama and Philippines.]

PLAN OF PARTITION WITH ECONOMIC UNION

PART I

Future constitution and government of Palestine

A. TERMINATION OF MANDATE, PARTITION AND INDEPENDENCE

1. The Mandate for Palestine shall terminate as soon as possible but in any case not later than 1 August 1948.

2. The armed forces of the mandatory Power shall be progressively withdrawn from Palestine, the withdrawal to be completed as soon as possible but in any case not later than 1 August 1948.

The mandatory Power shall advise the Commission, as far in advance as possible, of its intention to terminate the Mandate and to evacuate each area.

The mandatory Power shall use its best endeavours to ensure than an area situated in the territory of the Jewish State, including a seaport and hinterland adequate to provide facilities for a substantial immigration, shall be evacuated at the earliest possible date and in any event not later than 1 February 1948.

3. Independent Arab and Jewish States and the Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem, set forth in part III of this plan, shall come into existence in Palestine two months after the evacuation of the armed forces of the mandatory Power has been completed but in any case not later than 1 October 1948. The boundaries of the Arab State, the Jewish State, and the City of Jerusalem shall be as described in parts II and III below.

4. The period between the adoption by the General Assembly of its recommendation on the question of Palestine and the establishment of the independence of the Arab and Jewish States shall be a transitional period.

B. STEPS PREPARATORY TO INDEPENDENCE

1. A Commission shall be set up consisting of one representative of each of five Member States. The Members represented on the Commission shall be elected by the General Assembly on as broad a basis, geographically and otherwise, as possible.

2. The administration of Palestine shall, as the mandatory Power withdraws its armed forces, be progressively turned over to the Commission; which shall act in conformity with the recommendations of the General Assembly, under the guidance of the Security Council. The mandatory Power shall to the fullest possible extent co-ordinate its plans for withdrawal with the plans of the Commission to take over and administer areas which have been evacuated.

In the discharge of this administrative responsibility the Commission shall have authority to issue necessary regulations and take other measures as required.

The mandatory Power shall not take any action to prevent, obstruct or delay the implementation by the Commission of the measures recommended by the General Assembly.

3. On its arrival in Palestine the Commission shall proceed to carry out measures for the establishment of the frontiers of the Arab and Jewish States and the City of Jerusalem in accordance with the general lines of the recommendations of the General Assembly on the partition of Palestine. Nevertheless, the boundaries as described in part II of this plan are to be modified in such a way that village areas as a rule will not be divided by state boundaries unless pressing reasons make that necessary.

4. The Commission, after consultation with the democratic parties and other public organizations of The Arab and Jewish States, shall select and establish in each State as rapidly as possible a Provisional Council of Government. The activities of both the Arab and Jewish Provisional Councils of Government shall be carried out under the general direction of the Commission.

If by 1 April 1948 a Provisional Council of Government cannot be selected for either of the States, or, if selected, cannot carry out its functions, the Commission shall communicate that fact to the Security Council for such action with respect to that State as the Security Council may deem proper, and to the Secretary-General for communication to the Members of the United Nations.

5. Subject to the provisions of these recommendations, during the transitional period the Provisional Councils of Government, acting under the Commission, shall have full authority in the areas under their control, including authority over matters of immigration and land regulation.

6. The Provisional Council of Government of each State acting under the Commission, shall progressively receive from the Commission full responsibility for the administration of that State in the period between the termination of the Mandate and the establishment of the State’s independence.

7. The Commission shall instruct the Provisional Councils of Government of both the Arab and Jewish States, after their formation, to proceed to the establishment of administrative organs of government, central and local.

8. The Provisional Council of Government of each State shall, within the shortest time possible, recruit an armed militia from the residents of that State, sufficient in number to maintain internal order and to prevent frontier clashes.

This armed militia in each State shall, for operational purposes, be under the command of Jewish or Arab officers resident in that State, but general political and military control, including the choice of the militia’s High Command, shall be exercised by the Commission.

9. The Provisional Council of Government of each State shall, not later than two months after the withdrawal of the armed forces of the mandatory Power, hold elections to the Constituent Assembly which shall be conducted on democratic lines.

The election regulations in each State shall be drawn up by the Provisional Council of Government and approved by the Commission. Qualified voters for each State for this election shall be persons over eighteen years of age who are: (a) Palestinian citizens residing in that State and (b) Arabs and Jews residing in the State, although not Palestinian citizens, who, before voting, have signed a notice of intention to become citizens of such State.

Arabs and Jews residing in the City of Jerusalem who have signed a notice of intention to become citizens, the Arabs of the Arab State and the Jews of the Jewish State, shall be entitled to vote in the Arab and Jewish States respectively.

Women may vote and be elected to the Constituent Assemblies.

During the transitional period no Jew shall be permitted to establish residence in the area of the proposed Arab State, and no Arab shall be permitted to establish residence in the area of the proposed Jewish State, except by special leave of the Commission.

10. The Constituent Assembly of each State shall draft a democratic constitution for its State and choose a provisional government to succeed the Provisional Council of Government appointed by the Commission. The constitutions of the States shall embody chapters 1 and 2 of the Declaration provided for in section C below and include inter alia provisions for:

(a) Establishing in each State a legislative body elected by universal suffrage and by secret ballot on the basis of proportional representation, and an executive body responsible to the legislature;

(b) Settling all international disputes in which the State may be involved by peaceful means in such a manner that international peace and security, and justice, are not endangered;

(c) Accepting the obligation of the State to refrain in its international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity of political independence of any State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations;

(d) Guaranteeing to all persons equal and non-discriminatory rights in civil, political, economic and religious matters and the enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms, including freedom of religion, language, speech and publication, education, assembly and association;

(e) Preserving freedom of transit and visit for all residents and citizens of the other State in Palestine and the City of Jerusalem, subject to considerations of national security, provided that each State shall control residence within its borders.

11. The Commission shall appoint a preparatory economic commission of three members to make whatever arrangements are possible for economic co-operation, with a view to establishing, as soon as practicable, the Economic Union and the Joint Economic Board, as provided in section D below.

12. During the period between the adoption of the recommendations on the question of Palestine by the General Assembly and the termination of the Mandate, the mandatory Power in Palestine shall maintain full responsibility for administration in areas from which it has not withdrawn its armed forces. The Commission shall assist the mandatory Power in the carrying out of these functions. Similarly the mandatory Power shall co-operate with the Commission in the execution of its functions.

13. With a view to ensuring that there shall be continuity in the functioning of administrative services and that, on the withdrawal of the armed forces of the mandatory Power, the whole administration shall be in the charge of the Provisional Councils and the Joint Economic Board, respectively, acting under the Commission, there shall be a progressive transfer, from the mandatory Power to the Commission, of responsibility for all the functions of government, including that of maintaining law and order in the areas from which the forces of the mandatory Power have been withdrawn.

14. The Commission shall be guided in its activities by the recommendations of the General Assembly and by such instructions as the Security Council may consider necessary to issue.

The measures taken by the Commission, within the recommendations of the General Assembly, shall become immediately effective unless the Commission has previously received contrary instructions from the Security Council.

The Commission shall render periodic monthly progress reports, or more frequently if desirable, to the Security Council.

15. The Commission shall make its final report to the next regular session of the General Assembly and to the Security Council simultaneously.

C. DECLARATION

A declaration shall be made to the United Nations by the provisional government of each proposed State before independence. It shall contain inter alia the following clauses:

General Provision

The stipulations contained in the declaration are recognized as fundamental laws of the State and no law, regulation or official action shall conflict or interfere with these stipulations, nor shall any law, regulation or official action prevail over them.

Chapter 1

Holy Places, religious buildings and sites

1. Existing rights in respect of Holy Places and religious buildings or sites shall not be denied or impaired.

2. In so far as Holy Places are concerned, the liberty of access, visit and transit shall be guaranteed, in conformity with existing rights, to all residents and citizens of the other State and of the City of Jerusalem, as well as to aliens, without distinction as to nationality, subject to requirements of national security, public order and decorum.

Similarly, freedom of worship shall be guaranteed in conformity with existing rights, subject to the maintenance of public order and decorum.

3. Holy Places and religious buildings or sites shall be preserved. No act shall be permitted which may in any way impair their sacred character. If at any time it appears to the Government that any particular Holy Place, religious building or site is in need of urgent repair, the Government may call upon the community or communities concerned to carry out such repair. The Government may carry it out itself at the expense of the community or communities concerned if no action is taken within a reasonable time.

4. No taxation shall be levied in respect of any Holy Place, religious building or site which was exempt from taxation on the date of the creation of the State.

No change in the incidence of such taxation shall be made which would either discriminate between the owners or occupiers of Holy Places, religious buildings or sites, or would place such owners or occupiers in a position less favourable in relation to the general incidence of taxation than existed at the time of the adoption of the Assembly’s recommendations.

5. The Governor of the City of Jerusalem shall have the right to determine whether the provisions of the Constitution of the State in relation to Holy Places, religious buildings and sites within the borders of the State and the religious rights appertaining thereto, are being properly applied and respected, and to make decisions on the basis of existing rights in cases of disputes which may arise between the different religious communities or the rites of a religious community with respect to such places, buildings and sites. He shall receive full co-operation and such privileges and immunities as are necessary for the exercise of his functions in the State.

Chapter 2

Religious and Minority Rights

1. Freedom of conscience and the free exercise of all forms of worship, subject only to the maintenance of public order and morals, shall be ensured to all.

2. No discrimination of any kind shall be made between the inhabitants on the ground of race, religion, language or sex.

3. All persons within the jurisdiction of the State shall be entitled to equal protection of the laws.

4. The family law and personal status of the various minorities and their religious interests, including endowments, shall be respected.

5. Except as may be required for the maintenance of public order and good government, no measure shall be taken to obstruct or interfere with the enterprise of religious or charitable bodies of all faiths or to discriminate against any representative or member of these bodies on the ground of his religion or nationality.

6. The State shall ensure adequate primary and secondary education for the Arab and Jewish minority, respectively, in its own language and its cultural traditions.

The right of each community to maintain its own schools for the education of its own members in its own language, while conforming to such educational requirements of a general nature as the State may impose, shall not be denied or impaired. Foreign educational establishments shall continue their activity on the basis of their existing rights.

7. No restriction shall be imposed on the free use by any citizen of the State of any language in private intercourse, in commerce, in religion, in the Press or in publications of any kind, or at public meetings.3/

8. No expropriation of land owned by an Arab in the Jewish State (by a Jew in the Arab State)4/ shall be allowed except for public purposes. In all cases of expropriation full compensation as fixed by the Supreme Court shall be paid previous to dispossession.

Chapter 3

Citizenship, international conventions and financial obligations

1. Citizenship. Palestinian citizens residing in Palestine outside the City of Jerusalem, as well as Arabs and Jews who, not holding Palestinian citizenship, reside in Palestine outside the City of Jerusalem shall, upon the recognition of independence, become citizens of the State in which they are resident and enjoy full civil and political rights. Persons over the age of eighteen years may opt, within one year from the date of recognition of independence of the State in which they reside, for citizenship of the other State, providing that no Arab residing in the area of the proposed Arab State shall have the right to opt for citizenship in the proposed Jewish State and no Jew residing in the proposed Jewish State shall have the right to opt for citizenship in the proposed Arab State. The exercise of this right of option will be taken to include the wives and children under eighteen years of age of persons so opting.

Arabs residing in the area of the proposed Jewish State and Jews residing in the area of the proposed Arab State who have signed a notice of intention to opt for citizenship of the other State shall be eligible to vote in the elections to the Constituent Assembly of that State, but not in the elections to the Constituent Assembly of the State in which they reside.

2. International conventions. (a) The State shall be bound by all the international agreements and conventions, both general and special, to which Palestine has become a party. Subject to any right of denunciation provided for therein, such agreements and conventions shall be respected by the State throughout the period for which they were concluded.

(b) Any dispute about the applicability and continued validity of international conventions or treaties signed or adhered to by the mandatory Power on behalf of Palestine shall be referred to the International Court of Justice in accordance with the provisions of the Statute of the Court.

3. Financial obligations. (a) The State shall respect and fulfil all financial obligations of whatever nature assumed on behalf of Palestine by the mandatory Power during the exercise of the Mandate and recognized by the State. This provision includes the right of public servants to pensions, compensation or gratuities.

(b) These obligations shall be fulfilled through participation in the Joint economic Board in respect of those obligations applicable to Palestine as a whole, and individually in respect of those applicable to, and fairly apportionable between, the States.

(c) A Court of Claims, affiliated with the Joint Economic Board, and composed of one member appointed by the United Nations, one representative of the United Kingdom and one representative of the State concerned, should be established. Any dispute between the United Kingdom and the State respecting claims not recognized by the latter should be referred to that Court.

(d) Commercial concessions granted in respect of any part of Palestine prior to the adoption of the resolution by the General Assembly shall continue to be valid according to their terms, unless modified by agreement between the concession-holder and the State.

Chapter 4

Miscellaneous provisions

1. The provisions of chapters 1 and 2 of the declaration shall be under the guarantee of the United Nations, and no modifications shall be made in them without the assent of the General Assembly of the United nations. Any Member of the United Nations shall have the right to bring to the attention of the General Assembly any infraction or danger of infraction of any of these stipulations, and the General Assembly may thereupon make such recommendations as it may deem proper in the circumstances.

2. Any dispute relating to the application or the interpretation of this declaration shall be referred, at the request of either party, to the International Court of Justice, unless the parties agree to another mode of settlement.

D. ECONOMIC UNION AND TRANSIT

1. The Provisional Council of Government of each State shall enter into an undertaking with respect to economic union and transit. This undertaking shall be drafted by the commission provided for in section B, paragraph 1, utilizing to the greatest possible extent the advice and co-operation of representative organizations and bodies from each of the proposed States. It shall contain provisions to establish the Economic Union of Palestine and provide for other matters of common interest. If by 1 April 1948 the Provisional Councils of Government have not entered into the undertaking, the undertaking shall be put into force by the Commission.

The Economic Union of Palestine

2. The objectives of the Economic Union of Palestine shall be:

(a) A customs union;

(b) A joint currency system providing for a single foreign exchange rate;

(c) Operation in the common interest on a non-discriminatory basis of railways; inter-State highways; postal, telephone and telegraphic services, and port and airports involved in international trade and commerce;

(d) Joint economic development, especially in respect of irrigation, land reclamation and soil conservation;

(e) Access for both States and for the City of Jerusalem on a non-discriminatory basis to water and power facilities.

3. There shall be established a Joint Economic Board, which shall consist of three representatives of each of the two States and three foreign members appointed by the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations. The foreign members shall be appointed in the first instance for a term of three years; they shall serve as individuals and not as representatives of States.

4. The functions of the Joint Economic Board shall be to implement either directly or by delegation the measures necessary to realize the objectives of the Economic Union. It shall have all powers of organization and administration necessary to fulfil its functions.

5. The States shall bind themselves to put into effect the decisions of the Joint Economic Board. The Board’s decisions shall be taken by a majority vote.

6. In the event of failure of a State to take the necessary action the Board may, by a vote of six members, decide to withhold an appropriate portion of that part of the customs revenue to which the State in question is entitled under the Economic Union. Should the State persist in its failure to co-operate, the Board may decide by a simple majority vote upon such further sanctions, including disposition of funds which it has withheld, as it may deem appropriate.

7. In relation to economic development, the functions of the Board shall be the planning, investigation and encouragement of joint development projects, but it shall not undertake such projects except with the assent of both States and the City of Jerusalem, in the event that Jerusalem is directly involved in the development project.

8. In regard to the joint currency system the currencies circulating in the two States and the City of Jerusalem shall be issued under the authority of the Joint Economic Board, which shall be the sole issuing authority and which shall determine the reserves to be held against such currencies.

9. So far as is consistent with paragraph 2 (b) above, each State may operate its own central bank, control its own fiscal and credit policy, its foreign exchange receipts and expenditures, the grant of import licenses, and may conduct international financial operations on its own faith and credit. During the first two years after the termination of the Mandate, the Joint Economic Board shall have the authority to take such measures as may be necessary to ensure that–to the extent that the total foreign exchange revenues of the two States from the export of goods and services permit, and provided that each State takes appropriate measures to conserve its own foreign exchange resources–each State shall have available, in any twelve months’ period, foreign exchange sufficient to assure the supply of quantities of imported goods and services for consumption in its territory equivalent to the quantities of such goods and services consumed in that territory in the twelve months’ period ending 31 December 1947.

10. All economic authority not specifically vested in the Joint Economic Board is reserved to each State.

11. There shall be a common customs tariff with complete freedom of trade between the States, and between the States and the City of Jerusalem.

12. The tariff schedules shall be drawn up by a Tariff Commission, consisting of representatives of each of the States in equal numbers, and shall be submitted to the Joint Economic Board for approval by a majority vote. In case of disagreement in the Tariff Commission, the Joint Economic Board shall arbitrate the points of difference. In the event that the Tariff Commission fails to draw up any schedule by a date to be fixed, the Joint Economic Board shall determine the tariff schedule.

13. The following items shall be a first charge on the customs and other common revenue of the Joint Economic Board:

(a) The expenses of the customs service and of the operation of the joint services;

(b) The administrative expenses of the Joint Economic Board;

(c) The financial obligations of the Administration of Palestine consisting of:

(i) The service of the outstanding public debt;

(ii) The cost of superannuation benefits, now being paid or falling due in the future, in accordance with the rules and to the extent established by paragraph 3 of chapter 3 above.

14. After these obligations have been met in full, the surplus revenue from the customs and other common services shall be divided in the following manner: not less than 5 per cent and not more than 10 per cent to the City of Jerusalem; the residue shall be allocated to each State by the Joint Economic Board equitably, with the objective of maintaining a sufficient and suitable level of government and social services in each State, except that the share of either State shall not exceed the amount of that State’s contribution to the revenues of the Economic Union by more than approximately four million pounds in any year. The amount granted may be adjusted by the Board according to the price level in relation to the prices prevailing at the time of the establishment of the Union. After five years, the principles of the distribution of the joint revenues may be revised by the Joint Economic Board on a basis of equity.

15. All international conventions and treaties affecting customs tariff rates, and those communications services under the jurisdiction of the Joint Economic Board, shall be entered into by both States. In these matters, the two States shall be bound to act in accordance with the majority vote of the Joint Economic Board.

16. The Joint Economic Board shall endeavour to secure for Palestine’s export fair and equal access to world markets.

17. All enterprises operated by the Joint Economic Board shall pay fair wages on a uniform basis.

Freedom of transit and visit

18. The undertaking shall contain provisions preserving freedom of transit and visit for all residents or citizens of both States and of the City of Jerusalem, subject to security considerations; provided that each state and the City shall control residence within its borders.

Termination, modification and interpretation of the undertaking

19. The undertaking and any treaty issuing therefrom shall remain in force for a period of ten years. It shall continue in force until notice of termination, to take effect two years thereafter, is given by either of the parties.

20. During the initial ten-year period, the undertaking and any treaty issuing therefrom may not be modified except by consent of both parties and with the approval of the General Assembly.

21. Any dispute relating to the application or the interpretation of the undertaking and any treaty issuing therefrom shall be referred, at the request of either party, to the international Court of Justice, unless the parties agree to another mode of settlement.

E. ASSETS

1. The movable assets of the Administration of Palestine shall be allocated to the Arab and Jewish States and the City of Jerusalem on an equitable basis. Allocations should be made by the United Nations Commission referred to in section B, paragraph 1, above. Immovable assets shall become the property of the government of the territory in which they are situated.

2. During the period between the appointment of the United Nations Commission and the termination of the Mandate, the mandatory Power shall, except in respect of ordinary operations, consult with the Commission on any measure which it may contemplate involving the liquidation, disposal or encumbering of the assets of the Palestine Government, such as the accumulated treasury surplus, the proceeds of Government bond issues, State lands or any other asset.

F. ADMISSION TO MEMBERSHIP IN THE UNITED NATIONS

When the independence of either the Arab or the Jewish State as envisaged in this plan has become effective and the declaration and undertaking, as envisaged in this plan, have been signed by either of them, sympathetic consideration should be given to its application for admission to membership in the United Nations in accordance with Article 4 of the Charter of the United Nations.

PART II

Boundaries5/

A. THE ARAB STATE

The area of the Arab State in Western Galilee is bounded on the west by the Mediterranean and on the north by the frontier of the Lebanon from Ras en Naqura to a point north of Saliha. From there the boundary proceeds southwards, leaving the built-up area of Saliha in the Arab State, to join the southernmost point of this village. Thence it follows the western boundary line of the villages of `Alma, Rihaniya and Teitaba, thence following the northern boundary line of Meirun village to join the Acre-Safad sub-district boundary line. It follows this line to a point west of Es Sammu’i village and joins it again at the northernmost point of Farradiya. Thence it follows the sub-district boundary line to the Acre-Safad main road. From here it follows the western boundary of Kafr I’nan village until it reaches the Tiberias-Acre sub-district boundary line, passing to the west of the junction of the Acre-Safad and Lubiya-Kafr I’nan roads. From south-west corner of Kafr I’nan village the boundary line follows the western boundary of the Tiberias sub-district to a point close to the boundary line between the villages of Maghar and Eilabun, thence bulging out to the west to include as much of the eastern part of the plain of Battuf as is necessary for the reservoir proposed by the Jewish Agency for the irrigation of lands to the south and east.

The boundary rejoins the Tiberias sub-district boundary at a point on the Nazareth-Tiberias road south-east of the built-up area of Tur’an; thence it runs southwards, at first following the sub-district boundary and then passing between the Kadoorie Agricultural School and Mount Tabor, to a point due south at the base of Mount Tabor. From here it runs due west, parallel to the horizontal grid line 230, to the north-east corner of the village lands of Tel Adashim. It then runs to the north-west corner of these lands, whence it turns south and west so as to include in the Arab State the sources of the Nazareth water supply in Yafa village. On reaching Ginneiger it follows the eastern, northern and western boundaries of the lands of this village to their south-west corner, whence it proceeds in a straight line to a point on the Haifa-Afula railway on the boundary between the villages of Sarid and El Mujeidil. This is the point of intersection.

The south-western boundary of the area of the Arab State in Galilee takes a line from this point, passing northwards along the eastern boundaries of Sarid and Gevat to the north-eastern corner of Nahalal, proceeding thence across the land of Kefar ha Horesh to a central point on the southern boundary of the village of `Ilut, thence westwards along that village boundary to the eastern boundary of Beit Lahm, thence northwards and north-eastwards along its western boundary to the north-eastern corner of Waldheim and thence north-westwards across the village lands of Shafa ‘Amr to the south-eastern corner of Ramat Yohanan’. From here it runs due north-north-east to a point on the Shafa ‘Amr-Haifa road, west of its junction with the road to I’Billin. From there it proceeds north-east to a point on the southern boundary of I’Billin situated to the west of the I’Billin-Birwa road. Thence along that boundary to its westernmost point, whence it turns to the north, follows across the village land of Tamra to the north-westernmost corner and along the western boundary of Julis until it reaches the Acre-Safad road. It then runs westwards along the southern side of the Safad-Acre road to the Galilee-Haifa District boundary, from which point it follows that boundary to the sea.

The boundary of the hill country of Samaria and Judea starts on the Jordan River at the Wadi Malih south-east of Beisan and runs due west to meet the Beisan-Jericho road and then follows the western side of that road in a north-westerly direction to the junction of the boundaries of the sub-districts of Beisan, Nablus, and Jenin. From that point it follows the Nablus-Jenin sub-district boundary westwards for a distance of about three kilometres and then turns north-westwards, passing to the east of the built-up areas of the villages of Jalbun and Faqqu’a, to the boundary of the sub-districts of Jenin and Beisan at a point north-east of Nuris. Thence it proceeds first north-westwards to a point due north of the built-up area of Zir’in and then westwards to the Afula-Jenin railway, thence north-westwards along the district boundary line to the point of intersection on the Hejaz railway. From here the boundary runs south-westwards, including the built-up area and some of the land of the village of Kh.Lid in the Arab State to cross the Haifa-Jenin road at a point on the district boundary between Haifa and Samaria west of El Mansi. It follows this boundary to the southernmost point of the village of El Buteimat. From here it follows the northern and eastern boundaries of the village of Ar’ara, rejoining the Haifa-Samaria district boundary at Wadi’Ara, and thence proceeding south-south-westwards in an approximately straight line joining up with the western boundary of Qaqun to a point east of the railway line on the eastern boundary of Qaqun village. From here it runs along the railway line some distance to the east of it to a point just east of the Tulkarm railway station. Thence the boundary follows a line half-way between the railway and the Tulkarm-Qalqiliya-Jaljuliya and Ras el Ein road to a point just east of Ras el Ein station, whence it proceeds along the railway some distance to the east of it to the point on the railway line south of the junction of the Haifa-Lydda and Beit Nabala lines, whence it proceeds along the southern border of Lydda airport to its south-west corner, thence in a south-westerly direction to a point just west of the built-up area of Sarafand el’Amar, whence it turns south, passing just to the west of the built-up area of Abu el Fadil to the north-east corner of the lands of Beer Ya’Aqov. (The boundary line should be so demarcated as to allow direct access from the Arab State to the airport.) Thence the boundary line follows the western and southern boundaries of Ramle village, to the north-east corner of El Na’ana village, thence in a straight line to the southernmost point of El Barriya, along the eastern boundary of that village and the southern boundary of ‘Innaba village. Thence it turns north to follow the southern side of the Jaffa-Jerusalem road until El Qubab, whence it follows the road to the boundary of Abu Shusha. It runs along the eastern boundaries of Abu Shusha, Seidun, Hulda to the southernmost point of Hulda, thence westwards in a straight line to the north-eastern corner of Umm Kalkha, thence following the northern boundaries of Umm Kalkha, Qazaza and the northern and western boundaries of Mukhezin to the Gaza District boundary and thence runs across the village lands of El Mismiya, El Kabira, and Yasur to the southern point of intersection, which is midway between the built-up areas of Yasur and Batani Sharqi.

From the southern point of intersection the boundary lines run north-westwards between the villages of Gan Yavne and Barqa to the sea at a point half way between Nabi Yunis and Minat el Qila, and south-eastwards to a point west of Qastina, whence it turns in a south-westerly direction, passing to the east of the built-up areas of Es Sawafir, Es Sharqiya and Ibdis. From the south-east corner of Ibdis village it runs to a point south-west of the built-up area of Beit ‘Affa, crossing the Hebron-El Majdal road just to the west of the built-up area of Iraq Suweidan. Thence it proceeds southwards along the western village boundary of El Faluja to the Beersheba sub-district boundary. It then runs across the tribal lands of ‘Arab el Jubarat to a point on the boundary between the sub-districts of Beersheba and Hebron north of Kh. Khuweilifa, whence it proceeds in a south-westerly direction to a point on the Beersheba-Gaza main road two kilometres to the north-west of the town. It then turns south-eastwards to reach Wadi Sab’ at a point situated one kilometre to the west of it. From here it turns north-eastwards and proceeds along Wadi Sab’ and along the Beersheba-Hebron road for a distance of one kilometre, whence it turns eastwards and runs in a straight line to Kh. Kuseifa to join the Beersheba-Hebron sub-district boundary. It then follows the Beersheba-Hebron boundary eastwards to a point north of Ras Ez Zuweira, only departing from it so as to cut across the base of the indentation between vertical grid lines 150 and 160.

About five kilometres north-east of Ras ez Zuweira it turns north, excluding from the Arab State a strip along the coast of the Dead Sea not more than seven kilometres in depth, as far as Ein Geddi, whence it turns due east to join the Transjordan frontier in the Dead Sea.

The northern boundary of the Arab section of the coastal plain runs from a point between Minat el Qila and Nabi Yunis, passing between the built-up areas of Gan Yavne and Barqa to the point of intersection. From here it turns south-westwards, running across the lands of Batani Sharqi, along the eastern boundary of the lands of Beit Daras and across the lands of Julis, leaving the built-up areas of Batani Sharqi and Julis to the westwards, as far as the north-west corner of the lands of Beit Tima. Thence it runs east of El Jiya across the village lands of El Barbara along the eastern boundaries of the villages of Beit Jirja, Deir Suneid and Dimra. From the south-east corner of Dimra the boundary passes across the lands of Beit Hanun, leaving the Jewish lands of Nir-Am to the eastwards. From the south-east corner of Dimra the boundary passes across the lands of Beit Hanun, leaving the Jewish lands of Nir-Am to the eastwards. From the south-east corner of Beit Hanun the line runs south-west to a point south of the parallel grid line 100, then turns north-west for two kilometres, turning again in a south-westerly direction and continuing in an almost straight line to the north-west corner of the village lands of Kirbet Ikhza’a. From there it follows the boundary line of this village to its southernmost point. It then runs in a southernly direction along the vertical grid line 90 to its junction with the horizontal grid line 70. It then turns south-eastwards to Kh. el Ruheiba and then proceeds in a southerly direction to a point known as El Baha, beyond which it crosses the Beersheba-El ‘Auja main road to the west of Kh. el Mushrifa. From there it joins Wadi El Zaiyatin just to the west of El Subeita. From there it turns to the north-east and then to the south-east following this Wadi and passes to the east of ‘Abda to join Wadi Nafkh. It then bulges to the south-west along Wadi Nafkh. It then bulges to the south-west along Wadi Nafkh, Wadi Ajrim and Wadi Lassan to the point where Wadi Lassan crosses the Egyptian frontier.

The area of the Arab enclave of Jaffa consists of that part of the town-planning area of Jaffa which lies to the west of the Jewish quarters lying south of Tel-Aviv, to the west of the continuation of Herzl street up to its junction with the Jaffa-Jerusalem road, to the south-west of the section of the Jaffa-Jerusalem road lying south-east of that junction, to the west of Miqve Israel lands, to the north-west of Holon local council area, to the north of the line linking up the north-west corner of Holon with the north-east corner of Bat Yam local council area and to the north of Bat Yam local council area. The question of Karton quarter will be decided by the Boundary Commission, bearing in mind among other considerations the desirability of including the smallest possible number of its Arab inhabitants and the largest possible number of its Jewish inhabitants in the Jewish State.

B. THE JEWISH STATE

The north-eastern sector of the Jewish State (Eastern) Galilee) is bounded on the north and west by the Lebanese frontier and on the east by the frontiers of Syria and Transjordan. It includes the whole of the Hula Basin, Lake Tiberias, the whole of the Beisan sub-district, the boundary line being extended to the crest of the Gilboa mountains and the Wadi Malih. From there the Jewish State extends north-west, following the boundary described in respect of the Arab State.

The Jewish Section of the coastal plain extends from a point between Minat et Qila and Nabi Yunis in the Gaza sub-district and includes the towns of Haifa and Tel-Aviv, leaving Jaffa as an enclave of the Arab State. The eastern frontier of the Jewish State follows the boundary described in respect of the Arab State.

The Beersheba area comprises the whole of the Beersheba sub-district, including the Negeb and the eastern part of the Gaza sub-district, but excluding the town of Beersheba and those areas described in respect of the Arab State. It includes also a strip of land along the Dead Sea stretching from the Beersheba-Hebron sub-district boundary line to Ein Geddi, as described in respect of the Arab State.

C. THE CITY OF JERUSALEM

The boundaries of the City of Jerusalem are as defined in the recommendations on the City of Jerusalem. (See Part III, Section B, below).

PART III

City of Jerusalem

A. SPECIAL REGIME

The City of Jerusalem shall be established as a corpus separatum under a special international regime and shall be administered by the United Nations. The Trusteeship Council shall be designated to discharge the responsibilities of the Administering Authority on behalf of the United Nations.

B. BOUNDARIES OF THE CITY

The City of Jerusalem shall include the present municipality of Jerusalem plus the surrounding villages and towns, the most eastern of which shall be Abu Dis; the most southern, Bethlehem; the most western, Ein Karim (including also the built-up area of Motsa); and the most northern Shu’fat, as indicated on the attached sketch-map (annex B).

C. STATUTE OF THE CITY

The Trusteeship Council shall, within five months of the approval of the present plan, elaborate and approve a detailed Statute of the City which shall contain inter alia the substance of the following provisions:

1. Government machinery; special objectives. The Administering Authority in discharging its administrative obligations shall pursue the following special objectives:

(a) To protect and to preserve the unique spiritual and religious interests located in the city of the three great monotheistic faiths throughout the world, Christian, Jewish and Moslem; to this end to ensure that order and peace, and especially religious peace, reign in Jerusalem;

(b) To foster co-operation among all the inhabitants of the city in their own interests as well as in order to encourage and support the peaceful development of the mutual relations between the two Palestinian peoples throughout the Holy Land; to promote the security, well-being and any constructive measures of development of the residents, having regard to the special circumstances and customs of the various peoples and communities.

2. Governor and administrative staff. A Governor of the City of Jerusalem shall be appointed by the Trusteeship Council and shall be responsible to it. He shall be selected on the basis of special qualifications and without regard to nationality. He shall not, however, be a citizen of either State in Palestine.

The Governor shall represent the United Nations in the City and shall exercise on their behalf all powers of administration, including the conduct of external affairs. He shall be assisted by an administrative staff classed as international officers in the meaning of Article 100 of the Charter and chosen whenever practicable from the residents of the city and of the rest of Palestine on a non-discriminatory basis. A detailed plan for the organization of the administration of the city shall be submitted by the Governor to the Trusteeship Council and duly approved by it.

3. Local autonomy. (a) The existing local autonomous units in the territory of the city (villages, townships and municipalities) shall enjoy wide powers of local government and administration.

(b) The Governor shall study and submit for the consideration and decision of the Trusteeship Council a plan for the establishment of a special town units consisting respectively, of the Jewish and Arab sections of new Jerusalem. The new town units shall continue to form part of the present municipality of Jerusalem.

4. Security measures. (a) The City of Jerusalem shall be demilitarized; its neutrality shall be declared and preserved, and no para-military formations, exercises or activities shall be permitted within its borders.

(b) Should the administration of the City of Jerusalem be seriously obstructed or prevented by the non-co-operation or interference of one or more sections of the population, the Governor shall have authority to take such measures as may be necessary to restore the effective functioning of the administration.

(c) To assist in the maintenance of internal law and order and especially for the protection of the Holy Places and religious buildings and sites in the city, the Governor shall organize a special police force of adequate strength, the members of which shall be recruited outside of Palestine. The Governor shall be empowered to direct such budgetary provision as may be necessary for the maintenance of this force.

5. Legislative organization. A Legislative Council, elected by adult residents of the city irrespective of nationality on the basis of universal and secret suffrage and proportional representation, shall have powers of legislation and taxation. No legislative measures shall, however, conflict or interfere with the provisions which will be set forth in the Statute of the City, nor shall any law, regulation, or official action prevail over them. The Statute shall grant to the Governor a right of vetoing bills inconsistent with the provisions referred to in the preceding sentence. It shall also empower him to promulgate temporary ordinances in case the council fails to adopt in time a bill deemed essential to the normal functioning of the administration.

6. Administration of justice. The Statute shall provide for the establishment of an independent judiciary system, including a court of appeal. All the inhabitants of the City shall be subject to it.

7. Economic union and economic regime. The City of Jerusalem shall be included in the Economic Union of Palestine and be bound by all stipulations of the undertaking and of any treaties issued therefrom, as well as by the decision of the Joint Economic Board. The headquarters of the Economic Board shall be established in the territory of the City.

The Statute shall provide for the regulation of economic matters not falling within the regime of the Economic Union, on the basis of equal treatment and non-discrimination for all members of the United Nations and their nationals.

8. Freedom of transit and visit; control of residents. Subject to considerations of security, and of economic welfare as determined by the Governor under the directions of the Trusteeship Council, freedom of entry into, and residence within, the borders of the City shall be guaranteed for the residents or citizens of the Arab and Jewish States. Immigration into, and residence within, the borders of the city for nationals of other States shall be controlled by the Governor under the directions of the Trusteeship Council.

9. Relations with the Arab and Jewish States. Representatives of the Arab and Jewish States shall be accredited to the Governor of the City and charged with the protection of the interests of their States and nationals in connexion with the international administration of the City.

10. Official languages. Arabic and Hebrew shall be the official languages of the city. This will not preclude the adoption of one or more additional working languages, as may be required.

11. Citizenship. All the residents shall become ipso facto citizens of the City of Jerusalem unless they opt for citizenship of the State of which they have been citizens or, if Arabs or Jews, have filed notice of intention to become citizens of the Arab or Jewish State respectively, according to part I, section B, paragraph 9, of this plan.

The Trusteeship Council shall make arrangements for consular protection of the citizens of the City outside its territory.

12. Freedoms of Citizens. (a) Subject only to the requirements of public order and morals, the inhabitants of the City shall be ensured the enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms, including freedom of conscience, religion and worship, language, education, speech and press, assembly and association, and petition.

(b) No discrimination of any kind shall be made between the inhabitants on the grounds of race, religion, language or sex.

(c) All persons within the City shall be entitled to equal protection of the laws.

(d) The family law and personal status of the various persons and communities and their religious interests, including endowments, shall be respected.

(e) Except as may be required for the maintenance of public order and good government, no measure shall be taken to obstruct or interfere with the enterprise of religious or charitable bodies of all faiths or to discriminate against any representative or member of these bodies on the ground of his religion or nationality.

(f) The City shall ensure adequate primary and secondary education for the Arab and Jewish communities respectively, in their own languages and in accordance with their cultural traditions.

The right of each community to maintain its own schools for the education of its own members in its own language, while conforming to such educational requirements of a general nature as the City may impose, shall not be denied or impaired. Foreign educational establishments shall continue their activity on the basis of their existing rights.

(g) No restriction shall be imposed on the free use by any inhabitant of the City of any language in private intercourse, in commerce, in religion, in the Press or in publications of any kind, or at public meetings.

13. Holy Places. (a) Existing rights in respect of Holy Places and religious buildings or sites shall not be denied or impaired.

(b) Free access to the Holy Places and religious buildings or sites and the free exercise of worship shall be secured in conformity with existing rights and subject to the requirements of public order and decorum.

(c) Holy Places and religious buildings or sites shall be preserved. No act shall be permitted which may in any way impair their sacred character. If at any time it appears to the Governor that any particular Holy Place, religious building or site is in need of urgent repair, the Governor may call upon the community or communities concerned to carry out such repair. The Governor may carry it out himself at the expense of the community or communities concerned if no action is taken within a reasonable time.

(d) No taxation shall be levied in respect of any Holy Place, religious building or site which was exempt from taxation on the date of the creation of the City. No change in the incidence of such taxation shall be made which would either discriminate between the owners or occupiers of Holy Places, religious buildings or sites, or would place such owners or occupiers in a position less favourable in relation to the general incidence of taxation than existed at the time of the adoption of the Assembly’s recommendations.

14. Special powers of the Governor in respect of the Holy Places, religious buildings and sites in the City and in any part of Palestine. (a) The protection of the Holy Places, religious buildings and sites located in the City of Jerusalem shall be a special concern of the Governor.

(b) With relation to such places, buildings and sites in Palestine outside the city, the Governor shall determine, on the ground of powers granted to him by the Constitutions of both States, whether the provisions of the Constitutions of the Arab and Jewish States in Palestine dealing therewith and the religious rights appertaining thereto are being properly applied and respected.

(c) The Governor shall also be empowered to make decisions on the basis of existing rights in cases of disputes which may arise between the different religious communities or the rites of a religious community in respect of the Holy Places, religious buildings and sites in any part of Palestine.

In this task he may be assisted by a consultative council of representatives of different denominations acting in an advisory capacity.

D. DURATION OF THE SPECIAL REGIME

The Statute elaborated by the Trusteeship Council on the aforementioned principles shall come into force not later than 1 October 1948. It shall remain in force in the first instance for a period of ten years, unless the Trusteeship Council finds it necessary to undertake a re-examination of these provisions at an earlier date. After the expiration of this period the whole scheme shall be subject to re-examination by the Trusteeship Council in the light of the experience acquired with its functioning. The residents of the City shall be then free to express by means of a referendum their wishes as to possible modifications of the regime of the City.

PART IV

CAPITULATIONS

States whose nationals have in the past enjoyed in Palestine the privileges and immunities of foreigners, including the benefits of consular jurisdiction and protection, as formerly enjoyed by capitulation or usage in the Ottoman Empire, are invited to renounce any right pertaining to them to the re-establishment of such privileges and immunities in the proposed Arab and Jewish States and the City of Jerusalem.

* * *

Notes

1/ See Official Records of the second session of the General Assembly, Supplement No. 11, Volumes I-IV.

2/ This resolution was adopted without reference to a Committee.

3/ The following stipulation shall be added to the declaration concerning the Jewish State: “In the Jewish State adequate facilities shall be given to Arab-speaking citizens for the use of their language, either orally or in writing, in the legislature, before the Courts and in the administration.”

4/ In the declaration concerning the Arab State, the words “by an Arab in the Jewish State” should be replaced by the words “by a Jew in the Arab State”.

5/ The boundary lines described in part II are indicated in Annex A. The base map used in marking and describing this boundary is “Palestine 1:250000” published by the Survey of Palestine, 1946.

Annex A

Plan of Partition with Economic UnionAnnex B

City of Jerusalem

Boundaries Proposed By The Ad Hoc Committee On The Palestinian Question

[6]

WIKIPEDIA

THEODOR HERZL

[7]

WIKIPEDIA

DER JUDENSTAAT

DER JUDENSTAAT

THEODOR HERZL

[8]

WIKIPEDIA

BALFOUR DECLARATION

[9]

WIKIPEDIA

SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT

[10]

”His support for Israel wasn’t entirely without qualification, though: he famously said about the Balfour Declaration that “one nation solemnly promised to a second nation the country of a third,””

THE PHILADELPHIA JEWISH VOICE

ODE TO ARTHUR

EINDE ARTIKEL

TWEEDE ARTIKEL THE GUARDIAN:

The most memorable line about the Balfour declaration was composed by the Hungarian-born Jewish writer Arthur Koestler. With it, he quipped, “one nation solemnly promised to a second nation the country of a third”

THE GUARDIANTHE CONTESTED CENTENARY OF BRITAIN’S ”CALAMITOUS PROMISE”

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2017/oct/17/centenary-britains-calamitous-promise-balfour-declaration-israel-palestine

The British pledge to establish a ‘Jewish national home’ in Palestine is being celebrated and condemned as a divisive anniversary approaches. By Ian Black

Tue 17 Oct 2017 06.00 BSTLast modified on Mon 27 Nov 2017 15.20 GMT

Shares848

On the evening of Thursday 2 November, at an elegant but as yet undisclosed central London location, Theresa May will sit down for a festive dinner with Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and 150 other carefully selected VIP guests. They will be celebrating the historic promise, made a century ago to the day, that the British government would use its “best endeavours” to facilitate the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Security for the event will be tight and protesters will be kept well away. This is no ordinary anniversary.

Lose yourself in a great story: Sign up for the long read email

Read more

That 1917 pledge – known to posterity as the Balfour declaration – had fateful consequences for the Middle East and the world. It paved the way for the birth of Israel in 1948, and for the eventual defeat and dispersal of the Palestinians – which is why its centenary next month is the subject of furious contestation. After 100 years, the two sides in the most closely studied conflict on earth are still battling over the past.

Controversy dogged the declaration from the moment that Arthur Balfour, then foreign secretary, sent it to Lionel Walter, Lord Rothschild, who represented the British Jewish community. Its 67 words combined considerations of imperial planning, wartime propaganda, biblical resonances and a colonial mindset, as well as evident sympathy for the Zionist idea – embodied in the famous commitment to “view with favour the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people” in the Holy Land. It ended with two important qualifications: first, that nothing should be done to prejudice the “civil and religious rights” of Palestine’s “existing non-Jewish communities.” And second, that the declaration should not affect the rights and political status of Jews living in other countries.

This contested anniversary is a dangerous minefield for May’s embattled government. The prime minister has said she is looking forward to it – although the London dinner, as all those involved are anxious to emphasise, is deliberately being hosted not by her, but by the current Lords Rothschild and Balfour. In addition to the two prime ministers and other political heavyweights, invitees include the historian Simon Schama, who will deliver a public lecture on the subject the day before. Scores of other events are being organised by Jewish communities across the UK. Christian Zionists, who believe in the unerring power of biblical prophecy, are to celebrate at the Albert Hall under the slogan “Partners in this Great Enterprise”.FacebookTwitterPinterest The Balfour declaration of 1917. Photograph: Universal History Archive/UIG/Getty

Israel’s parliament, the Knesset, will hold a special session honouring Balfour, while British immigrants to the Jewish state are organising street parties to celebrate the day. In the US, the Israel Forever Foundation is urging supporters to “Stand with Balfour and make it YOUR declaration”. The original letter, kept in the British Library, may be loaned to Israel next year to mark the 70th anniversary of the country’s independence. In 2015 it was inspected by a reverential Netanyahu, who used the photo opportunity to call for a renewal of the “partnership” of 1917. (Netanyahu’s official residence, incidentally, is on Balfour Street in West Jerusalem. The address is used in the Israeli media, like Downing Street in Britain, as shorthand for its occupant.) A copy of Balfour’s letter is also on permanent display at the Yasser Arafat Museum in the West Bank town of Ramallah, seat of the Palestinian Authority and, since the 1967 war, occupied territory under international law.Advertisement

In London, Jerusalem and elsewhere, however, others will be commemorating and protesting what they condemn as an act of betrayal and perfidy, the “original sin” that led to injustice, war and disaster for the Palestinians in the Nakba (Arabic for “catastrophe”) of 1948. Two packed conferences took place on the same day in London in early October, with speakers lambasting British responsibility for continuing Palestinian suffering.

The Balfour Project – founded by clergymen and academics who want to see change in the UK’s Middle East policy – is holding a public meeting in Westminster on 31 October. Its slogan is: “Britain’s Broken Promise – Time for a New Approach”. But concern for the plight of the Palestinians is no fringe preoccupation. The former UN envoy to Syria, Lakhdar Brahimi – one of the Elders, a group of world leaders founded by Nelson Mandela in 2007 – is the biggest name on a Chatham House panel on Balfour. The British Academy is organising a seminar about the decision, which was described by the historian Elizabeth Monroe in the 1960s as “one of the greatest mistakes of our imperial history”. A London art gallery is running a series of events called “Turning the Page on the Balfour Declaration”, focusing on Arab culture and identity in Palestine before 1948. The centenary was debated in the House of Lords in July.

In an age when the conflict is increasingly waged by volunteer armies of social-media warriors, it should come as no surprise that both sides are determined to press their competing claims. The Balfour Apology Campaign is demanding Britain make amends for “colonial crimes” in Palestine. It is promoting a short film, 100 Balfour Road, which tries to explain the long-term effect of the declaration by showing the Joneses, an ordinary family in suburban London who are evicted from their home by soldiers and forced to live in appalling conditions in their back yard. Another family, the Smiths, take over their house and, supported by the soldiers, mistreat the Joneses and deprive them of food, medicine and their basic rights. The dissident group Independent Jewish Voices has produced a critical talking-heads documentary about Balfour – being circulated under the Twitter hashtag #NoCelebration.